Sales September

I spent 37 days doing nothing but talking to customers: cold-emailing, visiting shop floors, a trade show, and working in a Polish electronics factory.

Welcome to 40 new subscribers since my last email 👋🏼

At the end of August, I came back to Europe after building a chess robot in San Francisco. Two convictions crystallised: One, I can’t imagine working on anything but robotics; two, the road to general AI-based robots is way longer than I thought.

The summer sprint started as an idea to aggressively engage the biggest uncertainty: the technology. But with a newfound notion of where models stand, and who else is building, I realised that the question even more important than how can we build perfect AI for robots? is rather who wants them while they’re still imperfect?

The obvious thing to do in robotics is to push the technology forward. That’s why researchers dominate. But they’re solving a technology problem the only way they know how – with more research.

Brute-forcing the missing tech by raising massive funding is neither an inefficient strategy nor does it leverage Europe’s resources or my background. I’d rather build something people want now, even if imperfect, and let revenue fund the work to get it perfect.

In my last post, I mentioned that my big goal is to presell an application by the end of the year. After I wrote that, I kept thinking about how deadlines rarely survive first drafts. The most likely path to a year-end sale was to attempt one this month.

Once I started thinking about how, not whether, I’d do it, that notion was reinforced. I realised I didn’t actually know what exactly I’d be selling. I’d only ever seen one factory floor in my life. I had no idea what blue-collar work looked like day to day: what people actually did, what parts were valuable, hard, boring, or dangerous. I didn’t even know the job title of the person making those decisions, or how they thought about automation.

Realising how much you don’t know hurts. The subtle resistance to selling I had sensed before was probably my mind anticipating this pain.

Luckily, the pain is the moat. Everyone has to cross it. If I were to talk to customers, I’d have a leg up on those unwilling to confront the pain. With most competition coming from researchers, that should be a sizable chunk. The question was: how best to overcome that resistance? Again, overcorrection was the answer.

I called it Sales September. The plan was simple: a month of nothing but talking to customers. It turned into 37 days on the road through four countries, walking uninvited onto shop floors from Luxembourg to Zurich, spending a week on the line in a Polish electronics factory, getting rejected over and over, and hearing a few yeses that made up for all the noes 10 times over.

This post sums up what I learned and is meant to help anyone trying something similar do it even better.

I wanted to test 3 sales channels

This idea was motivated by the book Traction1. Cold email and trade shows were standard choices, but cold walk-ins weren’t. I don’t know of anyone still doing these, but since I was trying to see shop floors, I figured showing up in person would be necessary anyhow. Before I hit the road, though, I started with email2.

67 Cold emails led to 4 successful in-person meetings

I targeted owners/CEOs of manufacturing SMEs with 50–250 employees. The hypothesis: long-term incentives, willing to innovate, big enough to think about innovation, small enough to reply to emails like mine. I used Apollo.io3 to find relevant companies and checked Google Maps for nearby companies, thinking that I could cluster visits and thereby cut driving time. Boy, was I optimistic about reply rates.

My emails followed a simple two-paragraph structure: who I was (an ETH robotics researcher starting a company) and why I was writing (wanting to share SOTA robotics research with SMEs and learn about their automation experiences). I stressed that I had nothing to sell, which was technically correct.

Mass mailing would’ve been faster, but I wanted to detect reply patterns. I chose depth over speed, customising each message after scanning their site and Googling their name with “robotics” and other keywords. To speed up writing, I built a custom GPT with Dream Machines’ context and a few templates. My workflow: log key data in Notion (my CRM) → paste a screenshot for names/emails into GPT → dictate via voice note what customisation references I wanted and how to change tone.

Research + email iterations were slow, but full of small discoveries.

20-30 minutes per outreach was far too long and yielded low daily volumes. It felt so obviously slow and that was frustrating. But this initial over-meticulousness was helpful. Reading every website taught me more than I expected.

I got a sense of the average level of digitalisation a company had, which turned out to be a strong proxy for how open they’d be to robotics – especially when combined with in-person impressions. I began to see who I was writing to: mostly men over 50. Seeing their faces helped me simplify my technical language even further. I learned what the German SME landscape actually makes and saw for myself how notoriously niche the products of hidden champions are.

I stopped thinking of “manufacturing”, but of companies building aluminium housings for train door sensors, plastic trays for surgical instruments, custom coils for espresso machines, precision-cut gaskets for dairy pumps, or milled brass fittings for vintage car restorers.

Patterns emerged. Every industrial district, for example, has at least one plastics moulder, a metal workshop, and a logistics hub; electronics manufacturers are surprisingly rare. I also started to calibrate scale: a firm with 100 employees often operates on a far smaller site than I’d imagined. That small insight later helped me judge which sites were worth visiting cold in person.

A lucky two-day head start turned into a week of disappointment.

In the first 1.5 days4, I sent 25 emails and immediately woke up to two replies the next day. Wow! This was amazing. I kept writing emails until next Friday – with a few distractions such as creating business cards or learning about outreach tools – but this week was very different from the first three days: One reply turned into a phone call that was all but motivating.

The owner had forwarded the email to the ‘head of innovation’, and the essence of the call was “look buddy, I’m only taking this call because I’m in the car right now and my only alternative is the radio. I’ve been in this position for 6 months now, and while it sounds interesting what you’re building, I need something with quick results, and that’s definitely not you”.

I’d been sitting in my dark little room sending emails into the void for over a week now, and it felt like neither sales prospects nor learnings were accumulating. Was I wasting my time?

Seeing the results in the form of the conversations later, I can say that I definitely wasn’t (more on those successful interactions in the next section) but looking back a month later, I think these three changes will make the next iteration 2-5x more efficient.

Shorter emails, maybe link to videos: Classic start-up advice I ignored until I re-read my emails weeks later. The biggest perspective shift came from getting cold emails myself and consciously analysing my own reaction. Moreover, my IRL interactions showed me how videos explain in 15 seconds what I say in 15 minutes. Therefore, I’m considering linking to those in the emails. A cleaner solution might just be showing them on the homepage, as anyone remotely interested clicks on the link in the email footer.

My targeting was too broad: I was overly exploratory, emailing everything from metal and plastics to insect farms and kitchen furnishers. Visits revealed a ginormous variation in automation potential. Going forward, I’m focusing on small electronics manufacturers, where fit, urgency and value proposition are highest. While inefficient for outreach, making this mistake was probably a necessary step to learn.

Personalise smarter: 20–30 minutes per email was unsustainable, but personalisation did matter. The right balance: a) spend ~10 minutes for high-signal prospects (modern site, young owner, right product) and b) also build micro-campaigns to discover new sectors: same email sent to ~50 companies with example applications relevant to their industry. This makes things semi-personalised.

Biggest learning: A past automation attempt is the strongest signal you can have.

Most Google searches for automation news returned nothing. But occasionally I’d find an article like this one. Articles like those were gold. But not for the reason I thought, namely, easy personalisation.

3 of the 4 companies I ended up visiting via email had already tried to automate with a robotic arm … and failed. They’d overestimated what traditional robots could do and underestimated how much effort it takes to make them work.

And exactly that made them the perfect audience:

They had identified the pain: selling is easier if you don’t have to convince your customer that they have a problem in the first place,

They had budgeted for automation, and

They’d experienced firsthand how rigid and costly traditional systems are, making them receptive to the value of robots configured by demonstration, not code.

This feedback was delayed, and I only realised its importance after I had sent all emails. The second channel, fortunately, provided much faster feedback, which is what even made “noes” motivating.

51 cold in-person visits led to 11 successful shop floor visits

When I think of sales, I picture someone selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door. I wasn’t selling a vacuum cleaner, but with my robot under my arm, I couldn’t help but feel like a caricature of what people in the 1950s would have imagined a salesperson to look like in 100 years.

Showing up in person let me see the shop floors, understand the tasks I wanted to automate, and – much to my surprise – turned out to be the most successful channel to speak to potential users.

Cold visits weren’t too different from meetings scheduled via email

Scheduled or not, I entered the building armed with a Trossen arm and an iPad full of demo videos. A conversation would look like this:

I’d first (re)introduce myself and explain why I’m here: Robotics is fundamental to manufacturing in Europe – now and even more so for the next 50 years. AI-based robotics will inevitably change your business. I’ve noticed how distant the research world creating this technology is from the real economy you’re operating in. That’s why I’m travelling through central Europe, talking to dozens of companies like yours, to show how AI Robotics works and to understand problems I can focus on in my next development sprint.

Next, I’d explain how the tech works in 60 seconds and move on to showing videos as fast as possible, explaining details while they were playing. The first three were always the same:

Placing cogs on pins to explain how models handle variability

Hanging a jumper to show the ability to adapt to new, unexpected behaviour

After that, I’d play 3–10 more clips while answering questions that arose from the first three. After only 8-10 minutes, the conversation would then turn to them.

Showing videos was key

The videos almost always sparked ideas: my counterparts explained where their processes required flexibility or recounted past automation attempts, both good and bad.

Some immediately saw applications, others enjoyed the demos but weren’t sure how to use them. If a shop floor visit didn’t come up naturally, I nudged or asked directly. Usually, it worked; occasionally, company policy or special circumstances like a customer visit blocked it.

All of this, of course, assumed there was a conversation to begin with.

Getting past the secretary

This involved way more skill than anticipated. Early on, I’d just walk in and start explaining myself, talking far too long. After 11 visits, I saw patterns in the reactions and noticed this wasn’t working well.

I quickly stopped listening to music while driving and tuned in to sales tutorials I wouldn’t have touched a month ago5. I prepared a structure before going into my next visit, but both visits 12 & 13, then promptly showed how saying the prepared sentences was neither natural nor convincing. So from visit 14 to 22, I just practised in the car like a dunce rehearsing their own name before a party until it sounded natural.

By the end, confidence from successful visits made it easy to strip my introduction down to “Dominique Paul from Dream Machines, where can I find [CEO’s name]?”, delivered it in a kind and demanding voice as if they’d be expecting me. By the time it became clear there was no meeting, the CEO was already standing in front of me or on the phone. If the secretary rejected me and I saw an open door to the shop floor on my way back to the car, then I’d just walk in and try again.

What I’m coming to appreciate in these overcorrective sprints is that not improving is not an option. When you’re two weeks in, every “no” reminding you how bad you still are, and with nothing else on the schedule for three more weeks, the motivation to learn comes quickly. You can apply the video you watched before going to bed when you wake up, you can try out multiple strategies in a day, and the frequency allows you to draw connections you’d otherwise miss.

Talking to customers in person was crucial

Watching tasks live revealed complexities missed in conversation. Descriptions rarely tell the full story. A “simple” task often hides critical details: at a plastic wrap manufacturer, one roll swap seemed trivial until I saw the roll was three metres long, a metal shaft had to be removed, and the empty cardboard required five layers of tape to add friction.

Many use cases only emerged in context while walking down the shop floor. Pointing to a workstation and asking, “What are you doing here?” was often followed by “Oh yeah, that also might be interesting for you to look at”. Tasks that hadn’t come to mind in conversation suddenly became clear candidates. An example of this was at a battery pack manufacturer, where I saw a battery testing procedure that, together with a previous observation, started to form a pattern and is now the main use case I’m building for.

Observing work helped quantify the scale of each problem. For every task, I could ask how much time it consumed. Often, the production manager had to check with the person doing the work. Doing this over a call could feel intrusive – or might yield a made-up number. At a lighting manufacturer in Tübingen, a task I observed turned out to take just a few hours a week. At another company, a task I saw being done by one person normally required two FTEs. Even more so, when I asked the owner, he went on to explain how they actually had 4x the demand contracted for in two years’ time and would need to ramp up production… Automation for this task suddenly looked very sexy.

It’s bewildering how much of Europe still runs on… hands.

What was most memorable wasn’t the complexity of the machines, but the simplicity of the work left to people. Tasks that required thought to design, but endurance to perform.

One example was at a battery pack manufacturer where two FTEs would spend the day opening boxes, pouring batteries into a machine that’d sort them by voltage, and then put them back into another box. The production manager explained it to me like this:

“The most exciting time of the day for our colleagues here is when the trash is full, because they get to do something else for 2 minutes.”

At the same time, most of the companies I spoke to are having problems hiring. An employee leaving for retirement is a serious problem when you don’t know how to replace them. In one case, the owner explained how a job listing had been online for 5 months without even a single application:

“Nobody wants to do these jobs anymore, people rightly don’t think of them as future-proof. And many would rather do a comfortable office job and earn a bit less.”

That was incredibly motivating. Automation is often painted as a threat, but what I saw was the opposite: companies eager to hire, and workers wanting more meaningful work that had a future. For decades, automation has been rolled out by systems integrators looking in from the outside or only accessible to industry giants. The next wave, shaped by AI robotics, will be led from within by the people who know the work best.

Despair and hope in Germany

Factory owners and production managers sent wildly different vibes. Some were very negative, talking about slowing demand, Kurzarbeit, or, in one case, how China wasn’t just cheaper but also better. Ouch.

Others radiated high agency and can-do energy, with more risk appetite than some founders in Berlin or SF. One business owner was so excited to start automating that I worried I’d over-sold the tech, only for him to say, “Perfect isn’t necessary, let’s just get going and see how it works. You know, the tech will grow over time and we’ll grow with it” … ummm, have you somehow been reading the same tech blogs as I have?

Conversations like these made me optimistic about European industry and reminded me of the power of momentum: believing in a better future is what creates it.

The coolest part was connecting with entrepreneurs from a different generation and environment – yet thinking similarly – and using technology to build something new together. I couldn’t think of a cooler customer to build for. This contrast of conversations made me appreciate how important it is to just keep going during outreach and why dozens of “noes” are worth it for a single right “yes.”

One Trade Show without success

I had planned to attend two trade shows, but the second was cancelled shortly before it began – the organisers decided to switch to a biennial schedule, which seems to be a broader trend. In the end, I went to one: EMO, the world’s largest metal-processing trade show, attracting about 80,000 visitors, many working on much more than metal.

Seeing thousands of people from this industry in one room with their products on display helped build a picture in my head of what this industry was like, who was sitting on the other end of my unanswered cold emails and how that person thought of the world. Many middle-aged men from small to medium towns wearing jeans and tucked-in white shirts with the company logo on the collar.

This was the biggest trade show I’d ever been to. I couldn’t even walk through half of the halls within a day, and quickly understood why it was scheduled for a whole week. Just the machinery on display must have been worth approximately €2 billion. I made the first day about soaking up impressions and having informal conversations. On the second, I decided it was time to talk to potential customers.

Most booths were selling machines. The people buying them were the ones I needed to talk to. So I walked the floor with my iPad, ready to show demos, and started talking to whoever seemed promising. After about ten tries, I realised this wasn’t going to work.

I had no idea who I was talking to. The badges were too small to read, and even when I could make out the company name, it didn’t tell me whether they were a potential customer or how to pitch them.

Everyone at a trade show is trying to sell something. But there’s a difference between walking up to a booth – where you’re the one looking for a conversation – and being stopped in the aisle. The fact that I was trying to sell without a booth didn’t help signal importance. Those working for interesting companies would quickly brush me off, and those who were inclined to listen weren’t decision-makers or didn’t work for a company at all. Part of the problem was that I couldn’t tell until a few minutes into the conversation.

When I did cold visits, I knew who I wanted to talk to, and I knew I was helping them by showing them this technology, even when they said no. At the trade show, it felt like I was just pestering people.

That being said, I see how a booth with a demo could generate a lot of interest as robotics makes for great demos and at a fair like this one, you’ll have virtually no competition. Maybe next year.

All in all, I was glad to have gone. Beyond learning more about this sales channel

I met several builders and we exchanged experiences about approaching manufacturing customers. One computer-vision QA team stood out. QA is one of the strongest use cases I’ve seen in factory visits, but systems that require workers to present objects to a camera manually have limited value. Speaking with them sparked an idea: selling into companies that already run AI-vision QA could be compelling.

I found out about a grant programme that could help my customers cover the cost of working with me.

I bumped into Jannik, with whom I had briefly ideated last year.

Still, I left a day earlier than planned to fit in another two days of cold visits before heading East.

Working in a Polish electronics factory for a week

Warm introductions were most valuable. One of the first calls was with A., the father who built an electronics factory with approximately 80 employees in Poland and was one of the most technology-interested entrepreneurs I met6.

On our second phone call, he said, “Do you want to do an internship with us?”. Oh god, I thought, I didn’t make it clear that I’m founding a company. But as I tried to correct, he said, “I’m exaggerating, I mean, do you wanna come to [town] and do the job yourself for a bit?”. Hell yeah, he had understood exactly what I was trying to do.

Even more so, although we had never met, he invited me to stay at his house. His younger son, who also accompanied us, was not just interesting to talk to, but also enabled a lot of communication by translating German to Polish and vice versa.

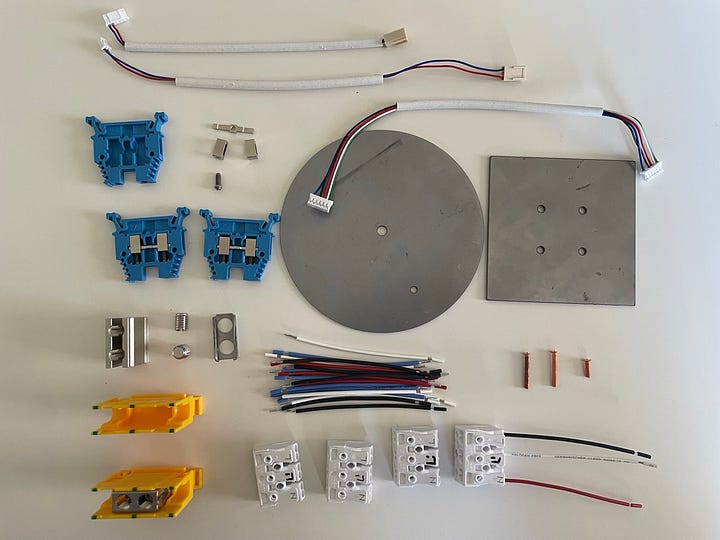

For one week, I did every single task of the production value chain myself: cable harnessing, metal processing, assembly, PCB testing, and more. Before, I had mostly talked to production managers and observed tasks. Now I was speaking for hours with the people doing the job, asked questions and even had some small inside jokes going on with them.

It’s hard to stay focused on doing most of the tasks for multiple hours straight.

Especially for the cables above, I’d sometimes slot the cable into the wrong hole. Fixing this takes 10x as long as creating a new one.

Doing shows you steps you cannot see.

When I observed a task for three iterations, I thought it was clear. But when I started doing them, new questions came up, or I made mistakes without noticing. Additionally, doing tasks for multiple hours shows you all the ‘extra’ steps associated: pouring out another batch of cable boxes, fetching a new box of PCBs from the shelf, refilling the screws in the box, and asking a co-worker where to find more cable ties. How would a robot handle any of this? In the long run, it should manage these steps autonomously, but until then, it needs a way to call for help. An SMS alert sounds obvious, but spending time there, I also learnt that phones are banned on the shop floor, so that’s not an option. These questions and details only became clear by being there for so long and not just watching. I now think it’d be stupid to sell & deploy a use case before having done it myself in the real environment for a few hours. There is so much you miss by working in a lab.

Doing developed a sense for precision and dexterity requirements.

For the metal bending example below, how firm do you have to hold the metal piece when the weight slides down? Could one robot arm be enough, or do you need both? How precise does the angle have to be to attain sufficient quality? Another example of something I never would have thought of: metal pieces are stacked next to the machine, but sometimes pieces stick together. How could a robot notice before bending two at the same time? How could you avoid this completely?

It’s what humans like doing that robots won’t be able to automate in the next 5 years.

In one metal workshop, the bending-machine operator walked us through a full hour of configuring new parts. It’s a chain of tiny measurement adjustments; even with perfect machine-state data, it simply isn’t automatable. Setting up the parts takes 30–120 minutes, and only then does the dull, repeatable production run for another 4–16 hours.

What struck me was how much the operator liked this phase. He described it as a puzzle – several interlocking steps, each demanding judgement and experience, almost like playing chess. It reminded me of the German CNC Milling Championship held at EMO, and how proficiency in this industry means understanding how to translate design to reality by bending a machine to your will and extruding maximum quality from it.

With what VLAs will be able to do – automating only the iterative, repetitive parts – skilled workers could scale their expertise instead of being replaced by it. You could imagine people in these roles earning six-figure salaries because one expert can now set up far more work. More broadly, automation at this level could trigger a wave of skilled worker-driven entrepreneurship by making small-batch production (lots of <10,000) economically viable.

The most unique part of this experience was spending so much time with A. Starting with the 6-hour drive back and forth from Berlin, sharing lunch, going to the gym together and having dinner every evening. It was this intensity of spending time together that helped me understand how an SME owner thinks about automation. We discussed specifics about unit economics, what cost structure (renting vs. buying) is more interesting to him, how he thinks about employee management, the relation to individual employees he has, what his cost structure is like, his concerns, and simply what he cares about and doesn’t.

6 other quick learnings

65€ for a night at a hotel is money well invested: The sleep quality alone beats a car, and it frees time for planning the next day’s route. Staying with friends is social, but a productive day depends on as many visits as possible, which need to be scheduled when visits aren’t feasible. Early hours shouldn’t eat into the main window. If I were to do it again, I’d follow this rhythm: start by replying to emails, hold scheduled calls from follow-ups to unsuccessful visits between 9-10 AM (visits aren’t ideal then7), then hit the road. 12-1 PM, when most are at lunch, is perfect for follow-ups – if a cold visit fails, you’ll often get their email. Maximise visits 1-4/5 PM, then use evenings for follow-ups again, planning the next day, and exercise.

Be clear about your intent and what the next step is. I initially had a clear goal: see the shop floor. But as I had more and more cases where customers were very enthusiastic about the product, I noticed that I didn’t have a plan for what was next. This is likely what salespeople mean by “Always Be Closing.” Asking them to buy felt premature. I was still understanding what my first use case would be. So, where did I want to steer our interaction? By the end, I had more clarity: I explained that I would run a development sprint on selected use cases and follow up in January with new demos. After that, we could have a call, I would visit again in person with a live demo, and they would then decide whether to enter a formal, paid pilot, with additional payments tied to reliability metrics. So my recommendation to anyone doing this would be to map out what you think your sales process should be step by step, so you can readily guide interested customers to the next step.

Switzerland might be uniquely positioned in global robotics. Companies in Basel and Zurich seemed unusually open to automation during cold visits, and the high manufacturing wages – 64% above Germany – might explain why. For what it’s worth, Switzerland is ranked #1 most innovative country, and ETH plus EPFL, Europe’s robotics leaders, are a unique talent pool + chance to speak with other robotics founders. Probably the best place to be building in robotics outside of China.

Now is a good time to plant the seed for inbound sales in 2027+. I enjoyed outbound far more than I expected, and I’m already looking forward to the second trip. But the biggest lesson was how stark the difference is between selling to people who already feel the need to automate and those who don’t yet see the pain. There’s no reliable way to detect the first group – you can’t scan for it – so the only real move is to make it easy for them to find you (similar to my experience with freelancing).

This could link well with an idea that’s been in the back of my mind: raising awareness among people not in the robotics community for what AI-based robotics is, how it works, and what it unlocks. I don’t think this is something that will drive any sales in the next 12 months, but it’s IMO important for society to become aware of it and also low effort to share what I’ve already learnt/built with others (as described in my last newsletter). This could compound into something bigger in 12+ months’ time and is then hard to replicate.GSheets beats Notion as a CRM. I initially tracked all emails in Notion to monitor reply rates and motivate myself with metrics (always trying to beat yesterday’s or last week’s numbers). The idea of one app for everything was appealing, but Notion didn’t work for this. I switched to Google Sheets, which was especially helpful for formulas to track when a follow-up was due.

Eat the frog. There was a resistance to the first cold email or cold visit each day. Once the first was done, it became addictive and I just wanted to keep going.

What’s next?

My only focus now is building a first version and putting it back in the hands of users by January – no matter how good or bad. For that, I’ve temporarily (?) moved to Zurich, where I’ll be collaborating with the ETH robotics club. More on that in my next post.

Speak to you soon.

Dominique

I posted daily updates on my X. You can find a collection of all posts that’s easier to read on my homepage here.

Thank you, Jannik, for lending me your Trossen arm. Thank you, Karim, Timo, and Constantin, for taking the time to share outreach strategies. Thank you, Simon, for showing me your family business and hosting me at your home. Thank you, York, Ilir, and Emanuel, for introducing me to the right people. Thank you, Ulrike & Frank and Moritz for hosting me. Thank you, A., for inviting me to Poland and offering to host me at your place even before we had met, and thank you, Julian, for the fun conversations and for translating between Polish and German.

Top Readings

Breakneck: China’s quest to engineer the future. You can now listen to Audiobooks on Spotify, and I listened to this one while driving in the car. It draws out a picture of the Chinese state being run by engineers, opposed to the US being run by lawyers, and explains how this influences how China works. Great summary of developments in China you normally don’t read about in standard media.

General Robots Newsletter: I noticed that I hadn’t shared this Substack in my last newsletter. After being laid off by Everyday Robots (Google Robotics) in 2023, Benjie wrote a series of posts explaining the challenges of robotics. The posts are entertaining to read and directed at a non-technical audience, but interesting for techies as well. I recommend starting with the first post.

All Roads Lead to Robotics: Eric Jang, head of AI at 1X, wrote an unstructured post on how he thinks robotics will play out. It doesn’t have the highest alpha, but I nevertheless found it interesting to understand how the 1X team thinks.

Ernesti, the initiator of Fr8 – the most interesting hacker house project in the world right now – wrote a great blog post reflecting on their first year and the journey so far. Fr8’s application window is open until November 30th.

AGI Sporks by Sergey Levine.

Apple in China: This book gets you so hyped about manufacturing. I’m listening to it, but I would have rather gotten it in print because I want more of the details to stick.

I’ve recently seen so many complaints about regulation in the EU in my feeds that I’m thinking this (cultural?) habit of using regulation as an excuse for one’s lack of agency is an even bigger problem. This essay by Armin Ronacher excellently summarises the problem. Thank you, Grzegorz, for sharing it.

Traction by Gabriel Weinberg, founder of DuckDuckGo, argues that startups rarely fail because they can’t build a product, but because they can’t get traction. This is hardly unique, but what I found so special about this book is that Weinberg, himself a technical founder, makes the book unusually practical: after outlining his core thesis in the first two chapters, he devotes the remaining 85% to concise, tactical overviews of 19 major growth channels. The central idea: for every startup, one channel is typically an order of magnitude better than the others. The goal is to discover that channel systematically by testing several in parallel, then doubling down on the one that works.

I didn’t know this, but your domain and email accounts actually need to be “warmed up” before you start sending real email campaigns; otherwise, your emails have a high chance of going to spam. Setting it up for 1 month is ideal. You can use tools to do this for you – I used Lemwarmup. Thank you, Robin, for the tip.

Which I highly recommend. It’s very convenient to filter by multiple criteria, gives you emails as well as phone numbers and has a generous free tier. Massimo and others have recommended Clay.io, but it felt like it was an unnecessarily powerful tool for what I was still doing.

I’m writing 1.5 because I initially started with cold calling, thinking this, together with an email, would make for a stronger reply rate. All numbers I found – this was before I found out about Apollo – were the front desk, which would exclusively tell me to write to info@companyname.com. I didn’t need more than a few of these calls to sense that this would be a waste of time, and switched to emailing directly.

It’s just a hunch, but I sometimes think Germans are held back by their own tradition of engineering. They expect the world to meet a certain standard before they act. The Poles, and others from emerging, fast-growing economies, seem more focused on what could be built next than on what’s possible right now. Xi Jinping put this quite well when he said that “China will always be a developing country”. Not talking about GDP, but that development never stops. More people in Europe, particularly Germany, could take a page out of that book.

A friend who had worked in a few of these jobs gave me some advice: “Don’t bother before 9 as most people are sorting out who’s sick, who got into a fight yesterday and which machine is broken. Friday afternoons can be lucky if you catch the owner at the right moment.”

That was a great first read of 2026! It really challenged my attention span, but it was joyful to be taken on the ride of starting something from scratch. I’ve done door to door sales, and oh boy it is fun but hard!

Happy to link you up with a few companies. Who knew chatting up with random people in cafes is also a viable discovery strategy

Love this!